Originally published in Points West magainze

Winter 2009

Cody’s Fairy Godmother: Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and her memorial sculpture, Buffalo Bill—The Scout

By Christine C. Brindza

Controversy is difficult to avoid in most large undertakings, and the creation of a Buffalo Bill memorial was no exception. When Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney accepted the commission to create a monumental tribute to Buffalo Bill, she prepared herself to take on the complicated task of memorializing one of the most famous American figures in history. She used both her artistic abilities and social status to produce and fund this work of art that would define a town, inspire a museum, and hold a place in American art and history. Her sculpture exceeded her wildest expectations.

A suitable memorial

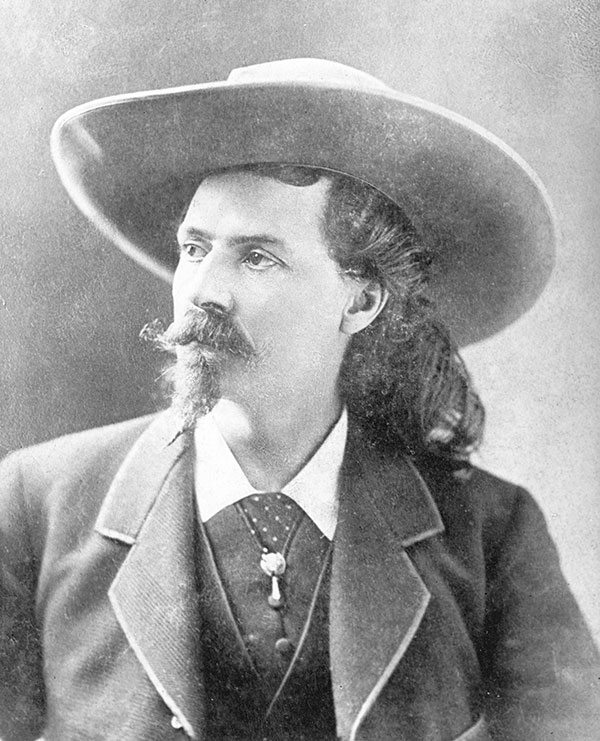

Upon the death of Colonel William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody in 1917, interest swept the nation to construct a memorial to the legendary western pioneer and Wild West showman. The location for the memorial site was logically within the town he founded: Cody, Wyoming. The spearhead organization, the Buffalo Bill Memorial Association, was formed to produce a fitting tribute to their founder and hero.

The Wyoming legislature appropriated $5,000, but the United States entered World War I in 1917, and the association refocused its efforts until the war ended. In 1921, the funds were re-appropriated: $4,000 for six and a half acres of land, two of which were to be set aside as a park where the memorial would stand.

Eventually, the idea of a memorial took the form of a sculpture, and the Memorial Association began the task of finding a suitable artist. Buffalo Bill’s niece Mary Jester Allen was first to personally approach Whitney for the commission. Allen, who lived in New York City at the time, received numerous letters from association trustees, coaxing her to contact the artist.

Another Cody area ranch owner, William Robertson Coe, a New York businessman and lover of western Americana, was also asked to contact Whitney, with whom he’d become acquainted in Long Island. He wrote to her, forwarding a letter from association member and author Caroline Lockhart, who explained the proposition. Lockhart, who soon became the owner of the Cody Enterprise, wrote, “The subject of a suitable memorial for Col. Cody is now agitating our peaceful village and I am writing to you to know if you would be interested in seeing if we could not a get a spirited and really good statue of Buffalo Bill on horseback done by somebody like Mrs. Harry Payne Whitney?”

When Allen visited Whitney and made the proposal, the artist agreed to the commission. Reflecting back on her visit, Allen recalled how Whitney reacted to the idea. “She had the entire thing right there. She never wanted ‘to do anything as much as this statue of her Wild West hero of her youth.’ She really wanted to do it, was already absorbed in her dream.”

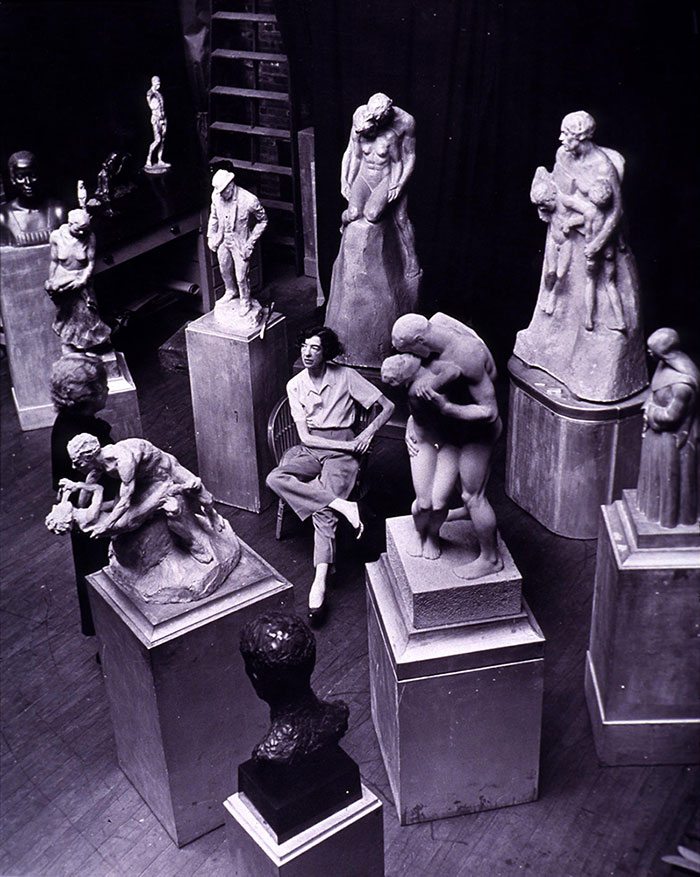

Whitney may have felt a small personal connection with Buffalo Bill. She saw his Wild West show in 1908, and the press referred to her as “the only woman sculptor with whom the Colonel was acquainted.” Still, she likely did not take the commission for personal reasons, but wanted to display her abilities in sculpture. She immersed herself in the subject by reading Buffalo Bill’s autobiography and other stories of the West. She studied equestrian sculpture, photographs of Buffalo Bill and cowboys, and planned to import a horse and rider as models.

Critics abound

Having a memorial—in a small town of 1,500 people—to one of the nation’s most well-known heroes, was simply remarkable, but to have such a well-connected sculptor undertake the project seemed even more so. If the Memorial Association wanted to bring attention and prestige to Cody, Wyoming, Whitney could make it happen. The attention that resulted, however, was not as expected.

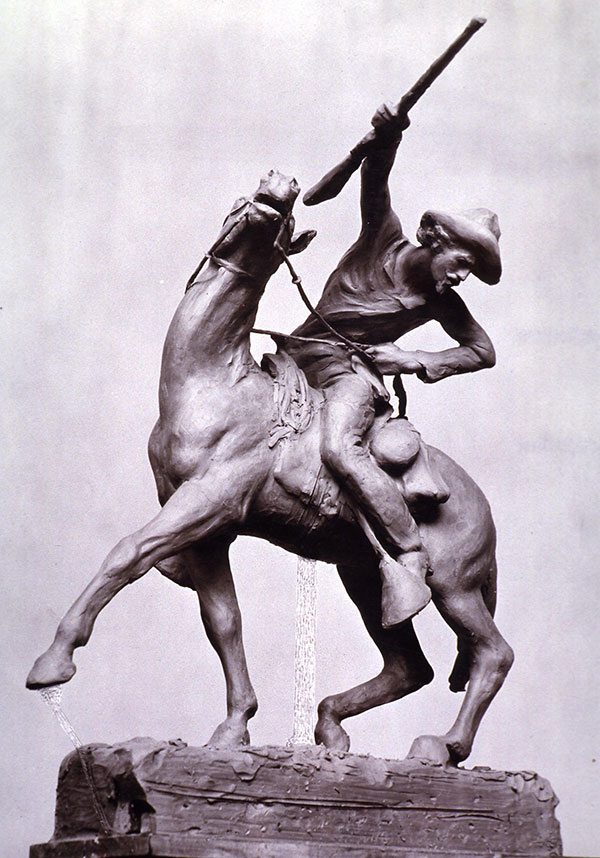

When Whitney announced that she finalized a model of the memorial sculpture, every detail of the work found scrutiny. Newspapers from Cody, Wyoming, to New York City recorded her progress by publishing articles about a purported controversy. Her concept for the memorial was to portray Buffalo Bill as a scout for the army, during an early part of his career. Whitney wanted to capture this hero pioneering the western frontier rather than the older and more mature Wild West showman. She envisioned the bronze sculpture on a granite plinth with a stream flowing nearby to symbolize Buffalo Bill’s contributions as an engineer and involvement in irrigation projects.

Whitney presented the Memorial Association with her proposal in January 1923. The model depicted Col. Cody as a scout on horseback, holding his ’73 Winchester in the air to signal troops to follow while peering down at a trail. By February, criticism of the model was a national sensation.

As recorded in an area newspaper at the time, when Whitney presented the Memorial Association with the small model of the sculpture, they were not completely satisfied. They agreed to accept the sculpture model if “the animal, including its tail, is ‘slenderized,’ its right hind foot brought down to earth instead of being permitted to coquet in the air, and a dent put in Col. Cody’s hat.” The horse was considered too “eastern” to be one that Buffalo Bill would have ridden. General Nelson A. Miles, for whom Buffalo Bill did his famous scouting, was also disappointed in the sculpture and thought the horse looked like it had been wounded in the neck—its position all wrong.

On May 20, 1923, The Philadelphia Inquirer published an article regarding the Association’s reaction in “Did Mrs. Whitney Go Wrong on Buffalo Bill’s Horse?” The author wrote how the Memorial Association “…could not conceal their disappointment in Mrs. Whitney’s conception of a western hero’s horse. They declared it was not a faithful representation of the type of mount Buffalo Bill always rode.” The article also mentioned other experts who were just as positive that Buffalo Bill’s horse might have been exactly like the one in Whitney’s model. Nevertheless, the Association wanted a realistic and, to them, a “historically accurate” portrait of Buffalo Bill and his horse—ideas that later they would say were only “suggestions.”

In pursuit of historical accuracy

Some say that Allen, in efforts to assist Whitney in obtaining“historical accuracy,” provided personal items of her uncle to the sculptor. “Even the clothes worn by the model were those worn by Buffalo Bill in his scouting days.” A proper “western” horse from Buffalo Bill’s TE Ranch outside of Cody was shipped out by train to New York City, along with two genuine “cowboys” sent along as proposed models. Smokey the horse was ridden back and forth through the city’s Central Park for Whitney’s observation.

Several accounts claimed that Lloyd and George Coleman, the cowboys who accompanied the horse to New York, were models for the Buffalo Bill figure. But an unidentified press release stated that they only took care of and rode Smokey when photographed for movement. Whitney used her own model for the actual sculpture. The model’s true identity remains a mystery.

Whitney may have felt that her artistic abilities were hindered if she made all of the requested adjustments, but she abided by her patrons’ wishes and made some changes. Even though satisfied with the final outcome of the work, Whitney seemed somewhat unsettled. She wrote in her journal after the debut of Buffalo Bill—The Scout in New York’s Central Park,“I happen to like my conceptions; I couldn’t do them if I didn’t. The fact that they always fall short of my ideals is painful… I suffer because I know they could be so much finer, but I enjoy because the child has been born and is my own.”

The home stretch

On July 9, 1922, Whitney had taken a train to Cody, Wyoming, to inspect the site for the sculpture, a location that she disliked. Instead she bought forty acres nearby in view of the Shoshone Canyon and the nearby red buttes, as well as Rattlesnake, Cedar, and Carter mountains. She also hired an architect, Albert R. Ross from New York, to design and construct the base of The Scout, to be built from natural materials found within the region. The architect contracted a local company, Kimball and Kimball Engineering, to build a “miniature Cedar Mountain” for the sculpture.

The stones used for the plinth were taken from the Shoshone Canyon located twenty-five miles away and weighed several tons each. Ross secured a dragline from Casper, Wyoming, a day’s trip at the time, and cement came from Billings, Montana, another day’s trip. In May 1924, Mrs. Juliana Force, Whitney’s trusted secretary, came to inspect the site and approved the base construction.

Cast at Roman Bronze Works in Brooklyn, New York, Buffalo Bill—The Scout was well received upon its debut. For one week in June 1924, it stood on display in New York City’s Central Park, placed near other portrait sculptures that included Beethoven and Shakespeare. The following week, the bronze sculpture—standing over twelve feet high—arrived by train in Cody, Wyoming. The town was quite excited when The Scout finally appeared on a flatbed railroad car. The work, first considered incorrect, was now hailed as a masterpiece. “It is an achievement upon which no one can look without a genuine glow of enthusiasm for it and its creator,” reported the Cody Enterprise. All criticism had died away.

The Buffalo Bill memorial’s unveiling took place on July 4, 1924, with an estimated 6,000 – 10,000 people attending. A time capsule was inserted in the base, where it remains to this day, and Jane Cody Garlow, Buffalo Bill’s granddaughter and the“prettiest girl in Cody,” pulled the cord to reveal the sculpture. Interestingly, Whitney did not attend the unveiling, but traveled to France instead as her focus moved to other commissions.

Not only did the townspeople of Cody consider the sculpture a masterpiece, it found international acclaim as well. Whitney’s model of The Scout, exhibited at the Paris Salon, received the “award of honor” by the French Government. Perhaps the suggestions given by the Memorial Association aided in Whitney’s success with the sculpture. Whitney wrote to Allen, “I want to thank you for all you have done for me, your keen interest in my work, your backing under all circumstances, and your loyalty to me has helped more than I can say…”

Within the next few years, a plan emerged for a museum to be placed within the vicinity of the Buffalo Bill memorial. In 1927, Mary Jester Allen opened the Buffalo Bill Museum adjacent to the sculpture. She continued correspondence with Whitney, and in the mid-1930s, traveled to New York to ask Whitney if she would consider one more donation: the property surrounding Buffalo Bill—The Scout to be used for future projects of the association. Whitney obliged and “…came like a Fairy Godmother and lay at our feet the things we most want and need,” wrote Mary Frost, president of the Wyoming Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs, on April 9, 1935.

Standing watch for eighty years

Juliana Force was contacted in 1936 regarding yet another proposal from Cody. This time, because of the gracious donations Whitney made to their town, the citizens planned to name an art colony after her. Force responded promptly, saying, “Although Mrs. Whitney was very sympathetic with any efforts of this kind, she very much disliked and objected to the idea of her name being used.” Whitney founded the Whitney Museum of American Art, an arts center in New York that was still in its infancy at the time, and wanted it to be kept an unassociated and distinct institution.

In the 1950s, when the Memorial Association wanted to use the land donated by Whitney, her son, Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney, became a large contributor to what would become the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, now the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. He donated over $250,000 in his mother’s memory to establish the Whitney Gallery of Western Art, dedicated in 1959, and Buffalo Bill—The Scout stood as the cornerstone of the collection. It is unknown if Whitney knew about his mother’s wishes regarding the use of her name, or, if so many years later, she would have minded at all.

The Scout has stood watch over his town for over eighty years—an idea that emerged as an iconographic image of the West and of the town of Cody, symbolizing both the memory of Buffalo Bill and the “western” ideals he represents. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney left her own mark on the nation, not only as one of the first women to successfully take on a monumental sculpture of this magnitude, but because of her other contributions in philanthropy and the arts. Without Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, there would be no Buffalo Bill—The Scout or Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

Through the vision of an artist and the drive of townspeople, a great dream became reality.

About the author

Christine Brindza is a former Curatorial Assistant, and Acting Curator of the Whitney Western Art Museum. She is now Curator at the Tucson Museum of Art. For a list of works cited, contact the editor.

Post 075