Hello again, and thanks for continuing to read the blog posts! This last owl-focused post is about a couple of amazing abilities that contribute to the awesome stealth of owls. Let’s get started!

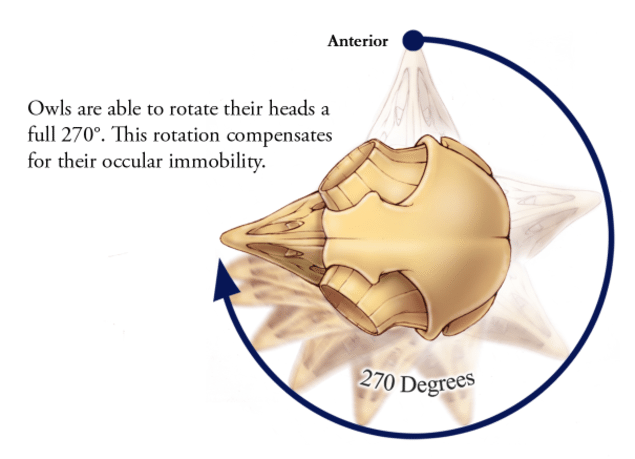

Owls are well known for that spooky ability to turn their heads “all the way around.” If you think about it though, that does not seem terribly realistic, no matter how cool. So while it is actually impossible, they do have an incredible range of motion around the neck: up to 270 degrees in either direction – that’s ¾ of the way around! When they move fast enough, it does look like they can go around all the way! This ability is really helpful for being stealthy, because the owl does not have to turn its whole body to use those great eyes that cannot move in their sockets or the incredible ears. Moving only the neck, they will make less noise and just make less movement to be noticed in general. Owls have a couple special adaptations in their neck to help them do that awesome trick: more bones than humans, special bone structures, and special veins.

The vast majority of mammals have only 7 neck bones, from the smallest mouse to the hugely tall giraffes, we all have only 7. Meanwhile, owls typically have 14 bones in their neck, which provides a lot of the previously mentioned flexibility. This is not unique to owls, though: the number of neck vertebrae that birds have vary greatly depending on the species. Owls have 14 neck, ostriches have 17, and swans have 23-25! Most birds have a huge range of motion in their necks, again due to the increased number of vertebrae – even if you’re not a kick-butt raptor, you still need to be able to see all around you and get to all the feathers on your body to make sure they’re in place!

The bone structure of those vertebrae are different than ours too: our bones have spines on each side and off the back of the bone that prevent turning more than 90 degrees, while owls only have spines on the back for the first three bones. Even the holes for the veins are larger, allowing more movement within the canals! Finally, when turning the neck so much, there’s one more problem: blood supply. In humans, the veins on our neck are sensitive, and if they get pinched, we lose consciousness quickly because there’s no blood going to the brain, and the brain panics!

Owls don’t have to worry about blood supply because they have reservoirs for blood right below the chin area. These are part of the normal system, pumping blood through the brain, and when they turn and the source vein gets pinched, there is still blood getting to the brain, and then the owl can turn back around and the blood will flow through like nothing happened; no panicking brain here!

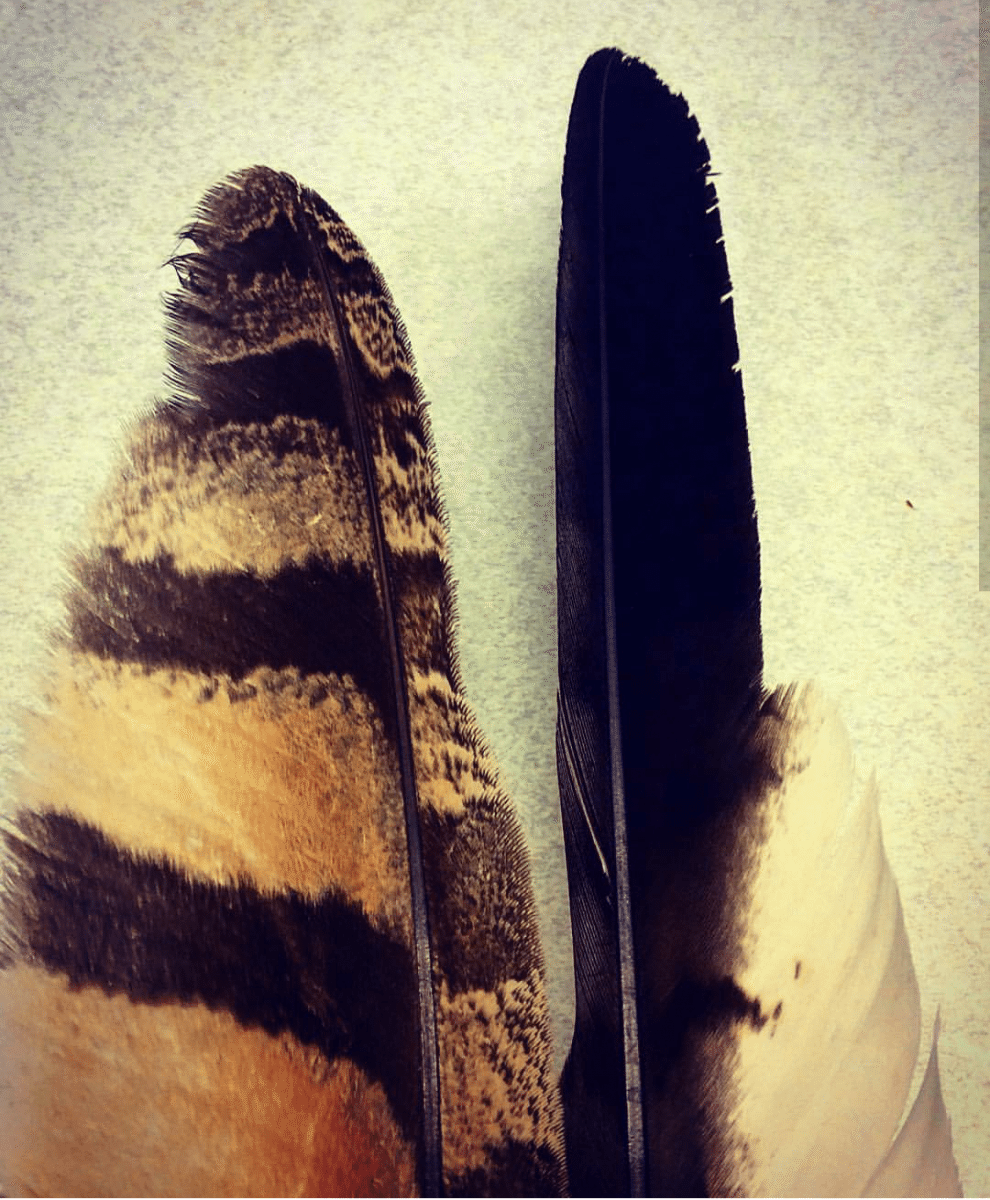

In case that is not a cool or complicated enough stealth ability for you, they do have one more stealth adaptation: silent flight. Many people who have had owls fly over their heads only feel the wind after the owl is already flying away! They need silent feathers so that when they fly, not only do their prey not hear them coming, but also so that their own flapping does not get in the way of their amazing hearing we talked about last time. To be so silent, owl feathers are incredibly soft, flexible, and have special edges!

Softer feathers means less friction and thus less noise as the owl glides down from the tree to snatch the mouse! Flexible feathers bend as they flap through the air, avoiding resistance and creating the draft of wind without the sound. Finally, as you saw in the picture above, the leading edge of the owl’s wing is fluted, looking kind of like the teeth of comb. This yet again decreases the turbulence of flight and thus allows the owls to fly almost silently, increasing their stealth abilities.

Check out this awesome BBC youtube video comparing flight between a pigeon, a peregrine falcon, and a barn owl! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d_FEaFgJyfA

Even with all of these super stealth abilities, it is so hard to be a predator! The success rates vary considerably across age groups and species: while learning to hunt, young owls may only be successful 15% of the time, or less! In one study, Short-Eared Owl adults were successful about 58% of the time, while another study on Eastern Screech Owls found their adults were only successful on 8 out of 35 attempts (22%)! Habitat also plays a role: in summer, when one group of Snowy Owls hunted lemmings on short vegetation tundra, they had almost a 100% success rate, while in winter with snow cover the success rate dropped to 58%.

Whatever the rates, it is a steep learning curve, and a tough life – but most of these birds have it covered. Hope you enjoyed these posts, thanks for tuning in!

References:

*Abbruzzese, Carlo M., and Gary Ritchison. The Hunting Behavior of Eastern Screech-owls (Otus asio). ResearchGate, January 1997. Found at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255602918_The_Hunting_Behavior_of_Eastern_Screech-owls_Otus_asio

*Potapov, Eugene, and Richard Sale. The Snowy Owl. A & C Black, Apr 25, 2013.

*http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/solving-the-mystery-of-owls-head-turning-abilities-9561557/?no-ist=

*Follow this link to see more about how owls turn their necks: https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/48681/how-can-owls-rotate-their-heads-270-degrees-without-dying