Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall/Winter 2014

Rough Riding with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

By Tom F. Cunningham

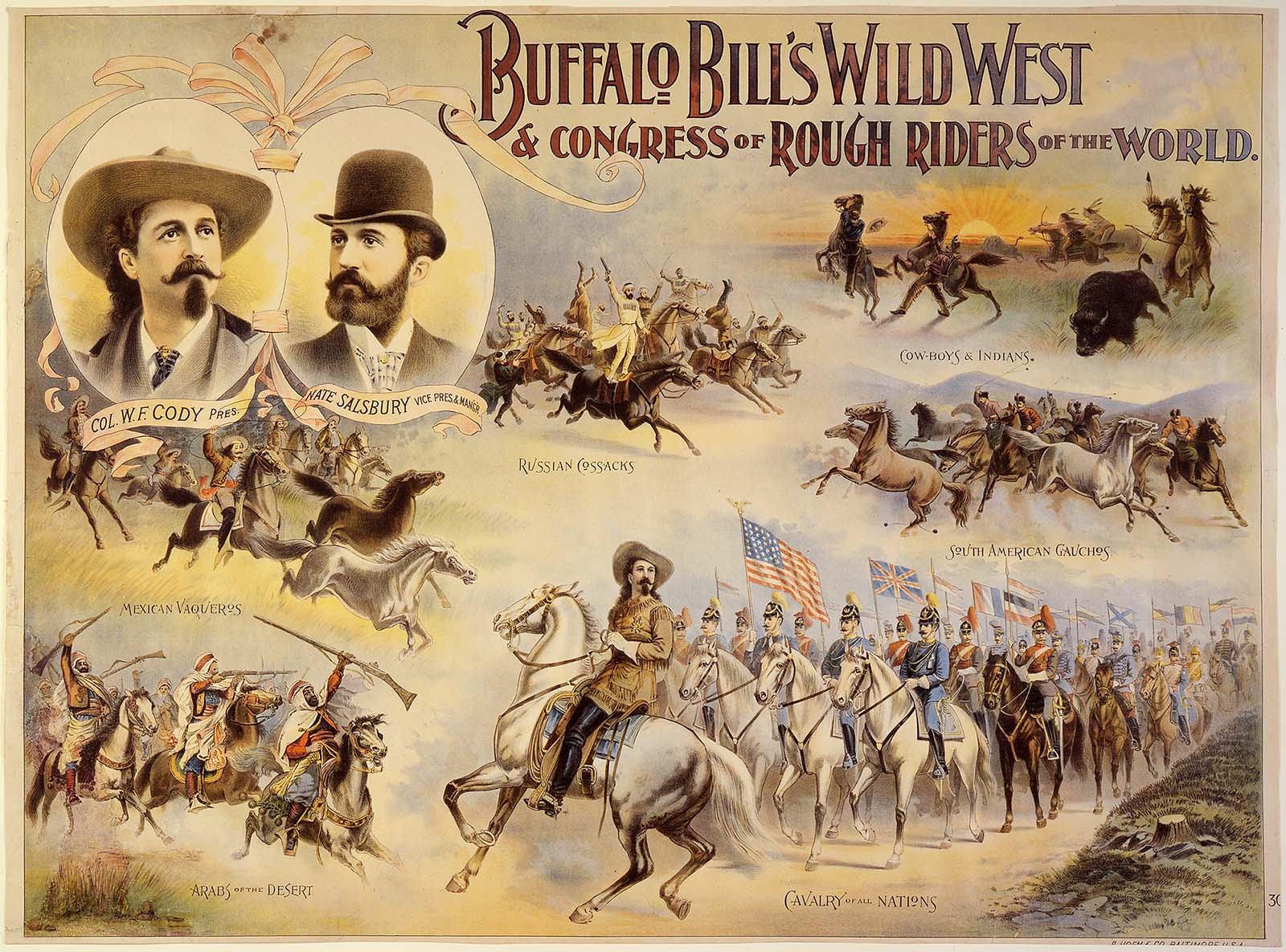

As organized in 1891, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West had 640 “eating members.” There were 20 German soldiers, 20 English soldiers, 20 United States soldiers, 12 Cossacks, and 6 Argentine Gauchos, which with the old reliables, 20 Mexican vaqueros, 25 cowboys, 6 cowgirls, 100 Sioux Indians, and the Cowboy Band of 37 mounted musicians, made a colorful and imposing Congress of Rough Riders. ~ Don Russell, The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill, 1960. University of Oklahoma Press

Scottish author and scholar Tom F. Cunningham has conducted extensive research—including study at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West—on Buffalo Bill’s Congress of Rough Riders. He takes issue with Russell’s numbers and dates, as well as other information proffered by Russell and other writers on the subject like Sam Maddras, Joseph Rosa and Robin May, Bobby Bridger, and Louis Warren, to name a few. Exactly how, why, and when were the Rough Riders incorporated into Buffalo Bill’s Wild West?

The facts, the conjectures, and the anecdotes confirm: These questions are tricky. For instance, consider the question of when the Rough Riders first appeared. Was it really 1891 as Russell indicates? Was it later? Possibly earlier? Cunningham’s goal is to point out the contradictions. But beyond that, he establishes the value of sound research and, along the way, demonstrates why a scholar wants to get the story right.

Those “extraneous features” in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

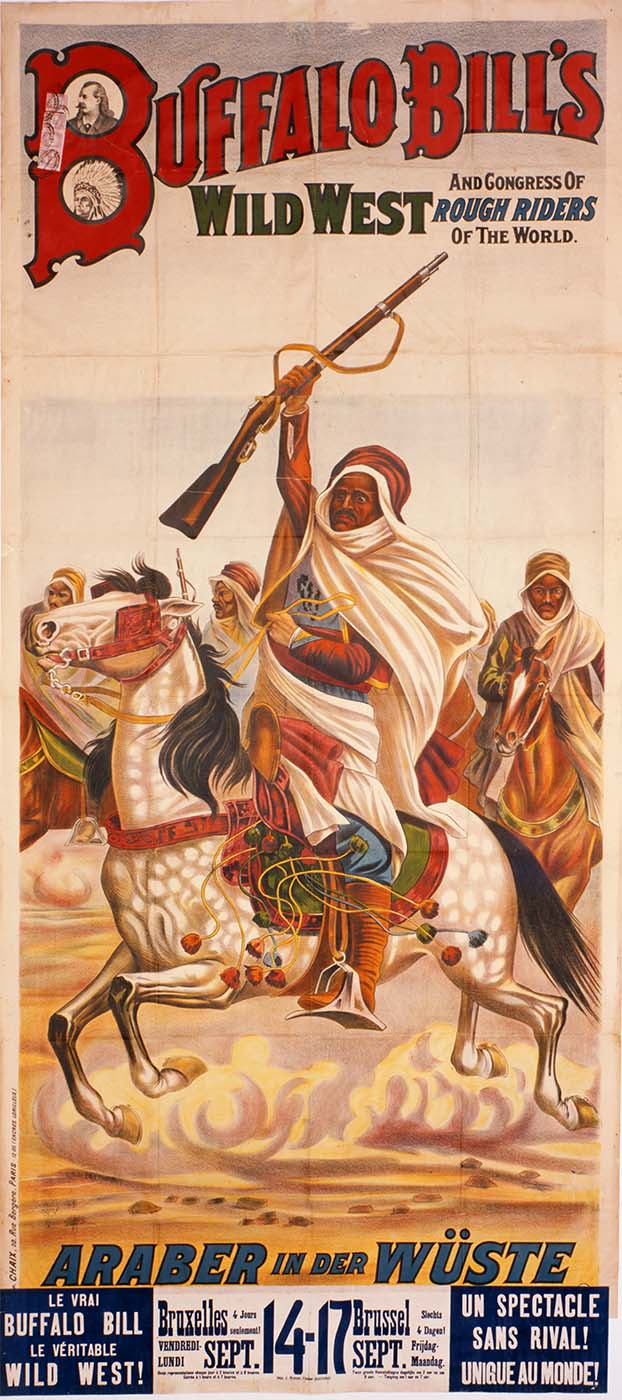

A further preliminary difficulty [with Russell’s assertion that the Rough Riders appeared in 1891] is that in his other major work on the subject, The Wild West—A History of the Wild West Shows, he repeats essentially the same story. Yet, unaccountably, he reproduces an image of a group of Bedouin Arabs with the show, captioned as having been photographed “in Vienna, Austria, in 1890.”

Henry Blackman and Victor Weybright Sell (Buffalo Bill and the Wild West) place Cossacks with the show as early as 1886. In an admittedly incidental paragraph of his book Standing Bear is a Person, Stephen Dando-Collins gives the clear impression that the Rough Riders of the World were an integral part of Cody’s show from the very outset, that is, in 1883. These various, unrelated, and isolated references raise at least the possibility that extraneous features in the Wild West, i.e. the Rough Riders, actually predated 1891.

Is that really the case?

The timing of this alleged momentous change in the composition of Buffalo Bill’s grand entertainment was, of course, far from fortuitous. Russell—also echoed by Rosa and May—explains that the new version of the show, devised by producer Nate Salsbury whilst in winter quarters at Benfeld, France, was a response to a threat which had arisen during the winter of 1891–1892. The show was, for a time, in peril of a permanent prohibition of the enlistment of American Indian performers. An alternative was therefore urgently required if the show was to continue in any recognizable shape or form.

Yet, in all the extensive newspaper coverage of the 1891 tour, and the subsequent winter stand in Glasgow, one cannot find a single mention of the international elements, with the solitary exception of the English soldiers, to whom I will return. The principal page of the official program for the 1891 English and Welsh venues lists seventeen standard Wild West items—not one of which discloses any hint that the human performers extended beyond the usual round of cowboys, Indians, Mexicans, and frontier girls.

In Glasgow, The Drama of Civilization, a chronological narrative depicting the conquest of the American frontier, was revived. If the “international elements” had been on hand, it seems entirely reasonable to inquire if a part was found for the Cossacks in the Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers sequence. Were the Germans staged as soldiers deployed in the re-enactment of Custer’s Last Stand? For that matter, could the Syrians have participated in the attack on the Deadwood Stage or the Emigrant Train? The official program for the Glasgow season fails to disclose any reference to the international acts.

In his insider’s view of the Wild West, Buffalo Bill: From Prairie to Palace, Major John M. Burke, Buffalo Bill’s general manager and press agent, makes a significant, though unspecific reference, to Salsbury’s activities while Salsbury was in charge of winter quarters during 1890–1891. Burke states that Salsbury’s “energy found occupation in attending to the details of the future.”

It is difficult to interpret this as referring to anything other than the laying of the foundation for the expanded company, and it has to be conceded that here is an obvious measure of support for Russell’s chronology. Nevertheless, contemporary sources make it abundantly clear that the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 loomed large on the horizon at the time, and there is nothing in Burke’s vague statement about Salsbury to require that he was referring to the immediate future, i.e. 1891.

No Indians for the Wild West?

In her contribution, Hostiles? The Lakota Ghost Dance and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, Dr. Sam A. Maddra begins by substantially reiterating the position popularized by Russell:

Despite the management’s outward optimism, the Wild West had taken very seriously the possibility of an Interior Department ban on the employment of Indians. Salsbury had revised the show in anticipation of such a ban. Until March 1891, there was no assurance that the Indians would be allowed to return to Europe, and as their role had been at the core of the show, management had to be prepared for a drastic reorganization. Salsbury had put into effect his idea of a show that “would embody the whole subject of horsemanship,” and had recruited equestrians from around the world, creating what was to become known as the Congress of Rough Riders.

Later, Maddra inserts an important qualification into the standard position, saying, “Cody’s success in obtaining the required Indian performers meant that the new show [complete with Rough Riders] delayed its debut until Buffalo Bill’s Wild West returned to London in May 1892.”

It may be that a contingency plan was in place to meet the crisis, but was put on hold when the ban was lifted, and Indian performers became available after all. Even better, the Indian contingent that year included twenty-three prisoners of war from the recent Ghost Dance disturbances. Since genuine “hostile” Indians were now participants, and Buffalo Bill had covered himself in superficial glory in their suppression, the Wild West show—far from going out of business—instead attained previously unscaled heights and found itself reinvigorated for another season at least.

Admittedly, it would be strange if, during the troubled period during which the Wild West was in imminent peril of losing its most essential performers, the Indians, no steps were taken to line up an alternative like the Rough Riders. A few months previous, in a November 19, 1890, interview with the New York Herald, Colonel Cody was reported to be exploring “Mexico, Peru, and other South American countries in search of cliff dwellers, Aztecs, Dodos, or any inanimate curiosity that will add strength to the big show he expects to manage in Chicago during the World’s Fair.”

With the Herald interview, it appears that although the crisis which threatened the supply of Indians had already arisen, Buffalo Bill had his sights firmly fixed on 1893.

Europe 1891

A proper consideration of the source materials reveals what is, beyond a shadow of doubt, the true sequence of events. Buffalo Bill’s spectacular, in the form in which it returned to Europe in the spring of 1891, was a Wild West show, pure and simple.

The first instance of a successful incorporation of extraneous elements came in Manchester, England, on the evening of July 31, 1891, when a performance was given for the benefit of local Crimean War veterans, of whom seventeen were then surviving. Alongside the usual Wild West program, performed in its entirety, the show began—for one night only—with a display sword exercises by a detachment of the 12th Lancers. The regimental band took the place of the Cowboy Band during the musical ride of the 12th, the troopers swinging their pennoned lances in accompaniment.

A company of “miniature volunteers,” consisting of boys ages 6–10, complete with a miniature brass band, gave an exhibition drill. The overall theme of the event appears to have been that of “past, present, and future”—a convention of the heroes of the past, the nation’s defenders of the present, and the soldiers of the future—some who were assuredly destined to meet their doom in the Great War, yet quarter of a century in prospect. Undoubtedly, there was some perceived parallel connecting the futile Charge of the Light Brigade to the doomed “heroism” of Custer’s Last Stand, and thus recommending it to the sympathies of Colonel Cody.

By the time the Wild West opened in Glasgow, Scotland, on Monday, November 16, 1891, the Congress of Rough Riders remained a work in progress, as evidenced by an article featured the day before in The World:

COL. CODY’S LATEST IDEA.

Buffalo Bill will exhibit what is left of his Wild West Show in Glasgow on Monday. He has revised his original plan to organize solely a Wild West Show for the Chicago Exhibition. He is now arranging to engage Russian Cossacks, German cavalrymen, and other types of daring horsemen from every country to exhibit in Chicago. Cody is now trying to arrange to test the popularity of his idea in London and Paris for one year before returning to America.

Europe 1892

The London trial run materialized the following summer, but the Paris trial did not. The working title of the revised spectacular around this time was “World Show of Rough Riders” according to the Alton Daily Telegraph, February 4, 1892.

By the middle of January 1892, Colonel Cody was preparing to return to the States, leaving his show to play in Glasgow in his absence for a few weeks longer; the number of Indians by this time was seriously depleted. The local press advertised that the show was recruiting “Stupendous Additional Attractions,” in order to soften the blow of Cody’s departure. These included a herd of six performing Burmese elephants and a group of thirty Schulis tribesmen from Central Africa. Cowboys now rode wild Texas steers, and a detachment of English Lancers performed sabre drills, no doubt recruited through contacts established earlier in Manchester.

On Friday, January 15, the new version of the show, operating under the banner of A New Era in History, was unveiled before an audience of invited guests. It opened to the public on Monday, January 18, 1892, and continued to run until the Glasgow season finally closed on Saturday, February 27. Only the Lancers went on to become a permanent feature; the Africans and the elephants were no more than a passing diversion intended to cover a temporary gap, an evolutionary dead end in the overall development of Buffalo Bill’s spectacular entertainment.

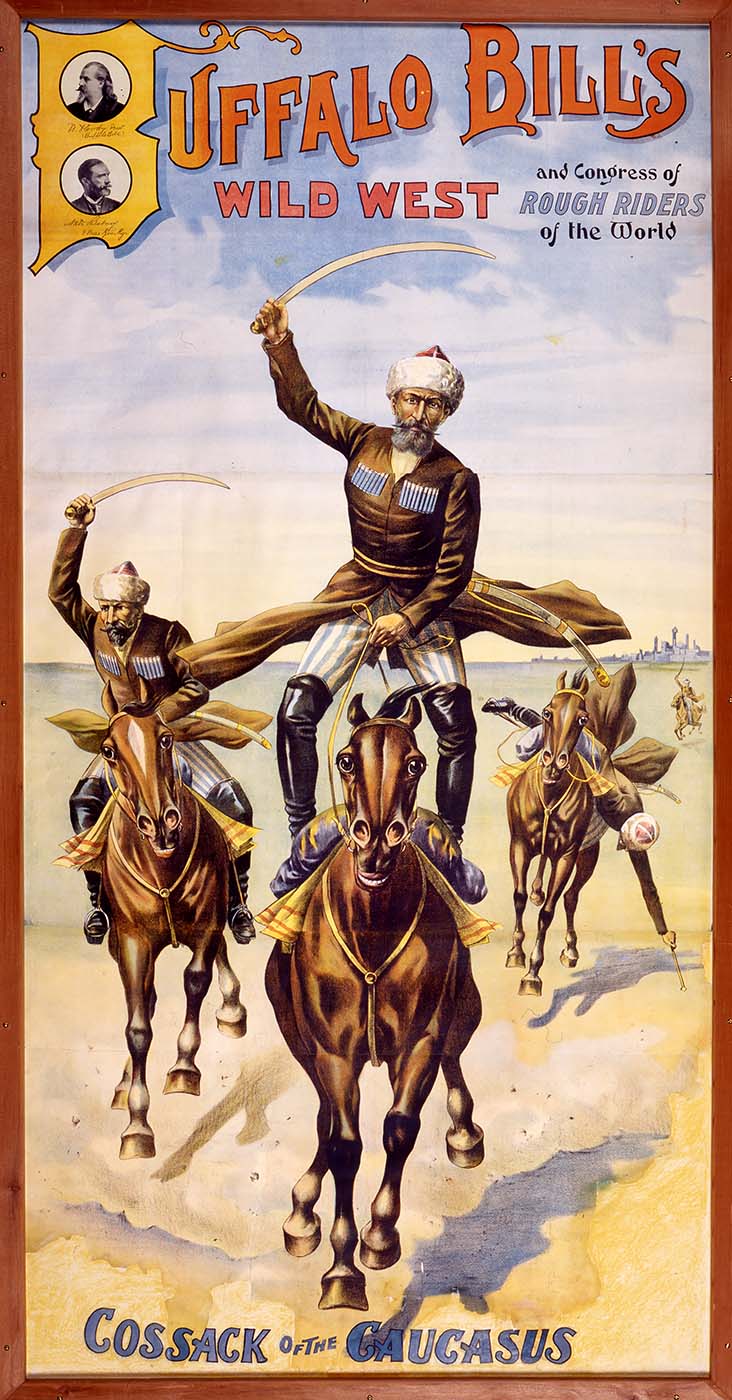

When the show re-opened in London as an adjunct of the International Horticultural Exhibition on May 7, 1892, it temporarily reverted to at least an approximation of the old Wild West format. However, a troupe of ten “Cossacks,” actually Georgians under the leadership of “Prince” Ivan Makharadze, followed by a band of gauchos from the Argentine, was added shortly thereafter. It is widely documented in the contemporary press that the “Cossacks” made their debut on Wednesday afternoon, June 1, 1892, and the gauchos on Thursday, June 23. Authors Makharadze and Chkhaidze, in Wild West Georgians, follow the same time scale.

Of the Cossacks, the Dundee Advertiser‘s May 23, 1892, edition narrated that “This is a portion of Buffalo Bill’s project of exhibiting at the ‘Wild West’ representative riders from all parts of the world.”

The Birmingham Post, June 10, 1892, made the overall strategy explicit:

Another addition has been made to Buffalo Bill’s “Wild West Show” at the Earl’s Court Horticultural Exhibition by the arrival of a band of South American Gauchos from the Argentine Republic. This makes the sixth contingent of horsemen of the world gathered by Colonel Cody for next year’s display at Chicago.

The first five contingents, it is presumed, were the cowboys, Indians, Mexicans, English Lancers, and Cossacks. The Lancers are problematic, though, as they appear to have received very little newspaper coverage, if any. However, Alan Gallop, in his Buffalo Bill’s British Wild West, provides clear photographic evidence that at least one English Lancer appeared in London in 1892. The insert to the 1892 Official Program makes no reference to the Lancers, but the one pictured in Gallop’s book probably made his appearance during Item No. 8 of the Wild West program, Across Country, with Riders of All Nations.

Nowhere in the abundant newspaper coverage of these developments is there any suggestion that the Cossacks or the gauchos were returning to the show after a period of absence—which would have been the case had they been part of the show in 1891. Rather, the context clearly requires that this was their first involvement with the Wild West, a fact positively emphasized by the show’s publicity materials.

For instance, the June 23, 1892, Morning Post unveiled the fresh arrivals with a modification to the standard advertisement:

First Visit to London of the

Sixth Delegation to Congress of Rough Riders of the World.

A band of South American Gauchos.

Meeting of Representatives of Primitive Schools of Horsemanship.

First time since the Deluge.

Of the Cossacks, the ad stated:

Cossacks of the Caucasus.

First Time in History.

Cossacks. Cossacks. Cossacks.

Cossacks. Cossacks. Cossacks.

A Sensation. A Novelty. A Success.

The show made no more significant additions during the remainder of the London season, but what had been accumulated thus far set the template for the new program it unveiled in 1893. Throughout 1892, the show’s official title remained simply Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, but the phrase “Congress of Rough Riders of the World” had begun to appear in advertisements in local papers. The opening item on the program was now Grand Review and introduction of the Rough Riders of the World.

Preparing for Chicago

Even the overwhelming majority of authors who endorse Russell’s view [that the expanded version of the show came into being in the spring of 1891], consistently concede that the banner of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World was probably not unfurled until the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. Warren writes:

In Europe, Cody, and probably Salsbury, too, had become aware of the mutual ideological resonance of American and Eurasian frontiers by 1891. The following year they added mounted contingents from “wild frontiers” beyond North America. In 1893, they formally reconstituted the show, expanding its narrative from western history to world history, under the new name “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World.”

In one of his more ambitious interpolations, Bridger states that on his return to Europe in the spring of 1891, Buffalo Bill found “Salsbury’s equestrian production” already in place and waiting for him. This implies a once and for all metamorphosis, as opposed to what was the reality—a gradual process of evolution over many months, involving at least an element of trial and error along the way.

The truth of the matter

The truth of the matter is neither ambiguous nor difficult to find for anyone willing to look beyond the standard texts to the abundant primary sources. What had been since its inauguration in 1883 a Wild West show plain and simple, gave the first hint of its initial, tentative steps in a new direction for one night only at Manchester, England, during the summer of 1891. A departure of sorts occurred in mid-January 1892 during the pivotal Glasgow winter season followed in June by the successive addition of fresh equestrian elements, on an experimental basis, during the London season.

It was not until the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 that Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World, in fact as well as in name, was launched, thus establishing the stable format under which, with periodic modifications, Buffalo Bill’s spectacular exhibition would continue to tour for several years thereafter.

About the author

A Scottish resident, Tom F. Cunningham is a graduate of Glasgow University in Scotland. For the past two decades, he has pursued an intensive study of Native American history with particular emphasis on connections to Scotland. He is the author of The Diamond’s Ace—Scotland and the Native Americans and Your Fathers the Ghosts—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Scotland. He also manages the Scottish National Buffalo Bill Archive, www.snbba.co.uk.

Post 290