Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2023

A Green River Journey: Pursuing the Perfect Vantage Point with Artist Tony Foster

By Karen Brooks McWhorter

On May 20, 2023, the Whitney Western Art Museum debuts the special exhibition Tony Foster: Watercolour Diaries from the Green River. Coordinated in partnership with the artist and The Foster Museum, the exhibition includes 16 paintings of locations on the Green River, whose source is in Wyoming.

Often referenced as the headwaters of the Colorado River system, the Green River is a critical western waterway of ecological and cultural significance.

For 40 years, Tony Foster has created paintings while on extensive journeys to some of the world’s wildest places. He often works at large scale, completing as much of his watercolors as possible in the field and never paints from photographs. He only finishes the paintings back in his studio in Cornwall, England.

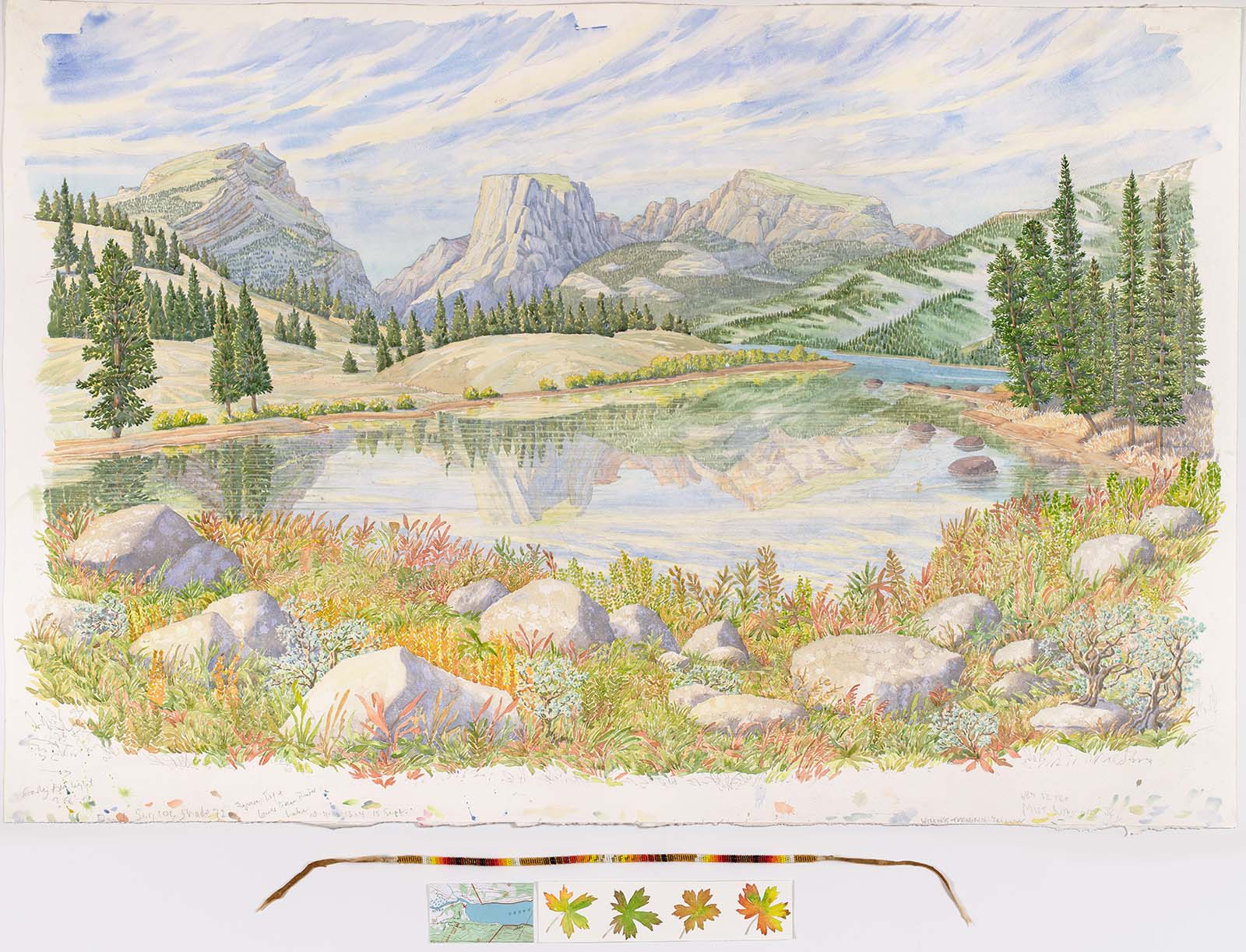

His beautiful and highly detailed works include handwritten notes, and are mounted with “souvenirs” like small sketches, collected or purchased objects, fossils, or bits of maps, all relating to his personal experiences of the places he depicts, as well as their histories.

Foster made most of his Green River paintings between 2018 and 2022, inspired by several trips to the American West during that time. On the last of these expeditions, I accompanied the artist and a film crew into the Wind River Mountains in west-central Wyoming. Foster came to paint a watercolor of Squaretop Mountain, and the film crew and I were there to offer him support and help document the project.

In mid-September of last year, our group gathered in Pinedale, Wyoming, at a popular campground near the outlet of Lower Green River Lake. That first evening out, Foster and I found ourselves several miles away from camp as the sun was setting, having tarried too long on the trail. I brought up the rear as Foster set a steady pace.

We kept conversation to a minimum, working hard to walk fast as the day darkened. Our boots padded rhythmically, and our hiking poles clicked against rocks. We heard little else. Atypically, there was none of Wyoming’s famous gusting wind, just a light breeze carrying intermittent birdsong.

The setting sun spurred us on, but also compelled repeated breaks to appreciate the valley’s beauty. Turning around, we faced Squaretop. From that northerly vantage point, it was framed by the timbered slopes of closer peaks. The mountain’s iconic, roughly rectangular profile was awash on its west face with a warm, peachy glow. Its east side and lower reaches were cast in pale lavender shadow. Haze from forest fires in nearby states had softened the palette to pastels.

As we approached the boundary of the Bridger Wilderness, we could see reflections of Squaretop and the surrounding mountains in Lower Green River Lake. The cloudless sky was azure blue, but fading fast. We made it back to camp with just enough light to set up a simple field kitchen, and we prepared rehydrated backpackers’ meals for dinner.

Squaretop stands sentry near the source of the Green, and represents the origin of the river in Foster’s series. The true source can be traced to snow fields and glaciers along the Continental Divide. In those highest elevations, the runoff lacks much definition until it accumulates in small lakes that lie above 10,000 feet in elevation. It then drops into Three Forks Park, where it is fed by other creeks. There, the river garners scale and substance until it empties into Upper and Lower Green River Lakes.

We raced sunset that evening because we lost track of time seeking the ideal site from which Foster could paint Squaretop. Before the trip, most in our group thought the perfect view might be from the shores of Upper Green River Lake, based on the many photographs people take from that spot. To vet the majority opinion, Foster gamely hiked there with us. Emerging from dense woods, we found a stunning vista—knee-high golden grasses ran up to the water’s edge. Across the lake and behind a handful of hills, Squaretop rose like an imposing citadel. As a testament to the scene’s beauty, a young couple was having their engagement photographs taken there. In part because of its popularity, the spot was less than appealing to Foster. Also, as a scene, it lacked complexity for pictorial composition. It is a straightforward view, with Squaretop at the center overpowering its surroundings.

“Nobody else has ever managed to find me a subject, no matter how hard they’ve tried,” Foster said with a smile as we sat around the campfire that night.

When we first arrived at our campground on Lower Green River Lake, Foster had walked around the northern shore and was surprised to quickly find a compelling site for his easel. From the Lower Lake’s outlet, Squaretop appears nestled between peaks of nearly equal size. Foster later confessed he was “suspicious” about having “hit on the right thing” so quickly. He cited another experience when it took him 16 days to settle on the right spot from which to paint the Grand Canyon.

Foster said that for him, site selection hinges on gut reaction, but also has as much to do with “formal requirements of a landscape painting as anything,” especially for larger works. One needn’t always follow the rules, though. “I don’t,” Foster said, “but there are certain circumstances where you just look at something—you know that’s going to work.”

Perhaps as impressive as Foster’s artistic eye and instinct was his sparse plein air painting gear. He has honed his field kit to just the essentials: one tiny paint box, one folding drawing board with the back routed out to reduce weight, a small plastic deli container lid to use as a mixing tray, and several brushes.

For his Squaretop painting, he unfurled a large piece of paper from an aluminum tube, clamping it to the drawing board with binder clips. He sat on a simple folding stool and got to work, sketching out the scene swiftly and skillfully. When he retired for the night, he replaced the painting with a simple, handwritten note: “Artist at work. Please leave alone. Thanks, Tony Foster.”

Armed with the experiences of many wilderness adventures, Foster arrived at the trailhead of this latest journey imminently prepared yet remarkably flexible, and guided by an earnest hope to inspire people to think about “the absolute exquisite complexity and interest” of the places he visits.

On our last night together in the Winds, as sparks from a crackling fire dissipated into the starry sky, we discussed our hopes for the exhibition.

I wanted the project to inspire appreciation for a unique Wyoming wilderness area, and to introduce visitors to Foster’s passion, talent, and vision—and his ability to connect us with nature.

Foster said that this journey, as part of his life’s work, was “about looking at things in depth and thinking about them over a long period, and studying them, and trying to convey the sense of what it’s actually like to sit in a place… absorbing the place.”

When so many of us have become increasingly disassociated with the natural world, and we are driven to look and think quickly instead of deliberately, Foster’s work encourages us to slow down and recognize, thoughtfully, the value of wild places like the Green River. His work invites our curiosity about what makes his landscape subjects unique, and why we should care.

Watercolour Diaries from the Green River runs concurrently with another special exhibition, Alfred Jacob Miller: Revisiting the Rendezvous—in Scotland and Today, coordinated by the Buffalo Bill Center of the West and the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art. Both of these shows invite visitors to experience Wyoming’s Green River through art, artifacts, and stories.

About the author

Karen Brooks McWhorter is Director of Curatorial, Education, and Museum Services for the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, and co-curator of the special exhibition Tony Foster: Watercolour Diaries from the Green River.

Post 348