Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2008

Staying Afloat in the 1890s: Buffalo Bill’s Financial Woes

By Jack Rosenthal

Guest Author

As any entrepreneur is sure to attest, the challenges of managing a business enterprise are substantial. The Great Showman himself, William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, faced those trials as he traveled with his Wild West show on the one hand and worked to develop the community of Cody, Wyoming, on the other. Jack Rosenthal discusses those difficulties in the story that follows, which is based on a series of letters he recently donated to the McCracken Research Library.

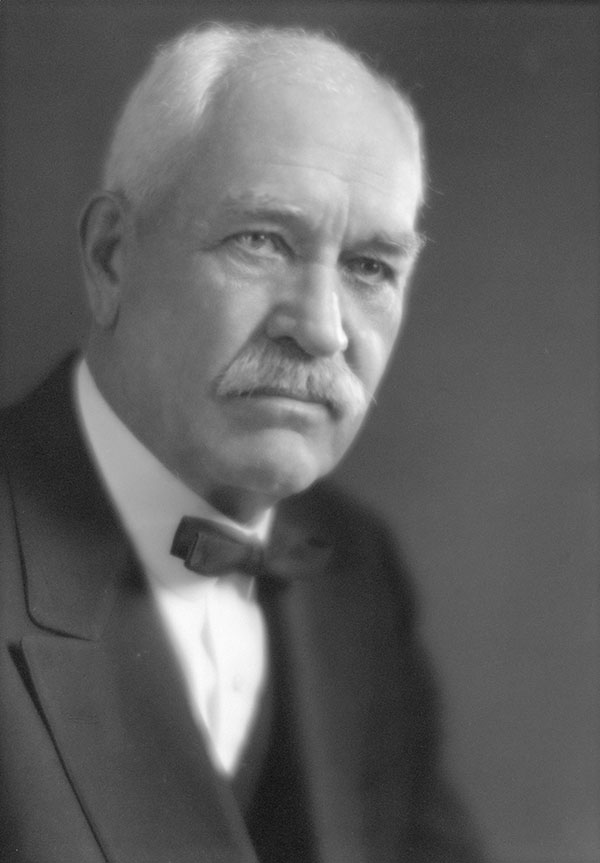

Newly uncovered correspondence from the 1890s and early 1900s reveals the extent of the financial hurdles experienced by the founders of the town of Cody, Wyoming. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and George Washington Thornton Beck were the principals in the development of the town site and in its early public utilities.

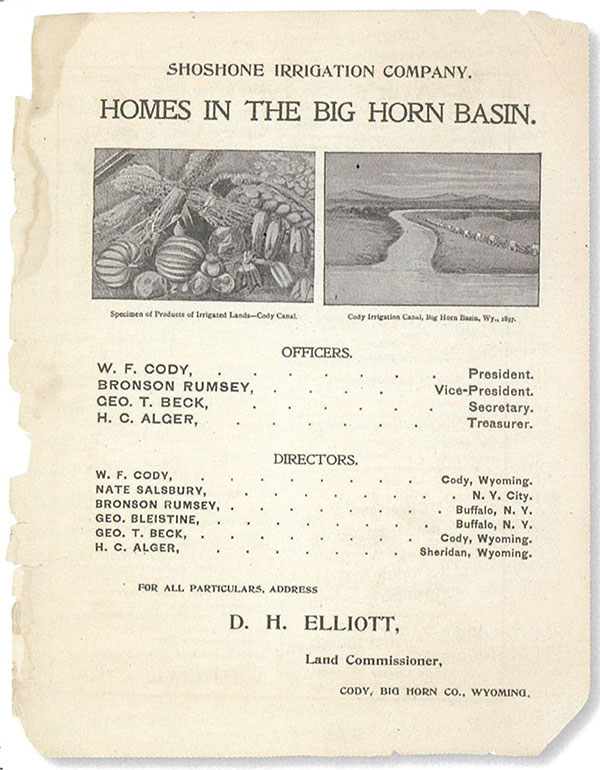

Beck’s father, U.S. Senator James B. Beck of Kentucky, served in Washington, D.C., with fellow Democratic Senator George Hearst of California. The new correspondence cites inability of the Shoshone Land and Irrigation Company—of which Cody and Beck were a part—to make timely payments on corporate and personal notes and bonds held by Phoebe Hearst, the wife of Senator Hearst and the mother of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst.

Mrs. Hearst had previously advanced funds to the irrigation company, which embarked on the construction of the Cody Canal to bring water to the new community. The first advance of Hearst funds was made in 1897 after two construction seasons had left the project and its partners in desperate straits. In Washington, it was Beck who had made the successful personal appeal to Phoebe Hearst after other lenders turned them down.

By that time, Senator Hearst, who died in 1891, had left his widow—twenty-two years his junior—the sole heir to a vast mining fortune. Mrs. Hearst, sensitive to the Beck/Hearst U.S. Senate relationship, coupled with the notoriety and popularity of the “Wild West” impresario Buffalo Bill, endeavored to assist financially in the development of the new town. But those responsible for managing her finances attempted to keep the dealings on a “businesslike basis,” no matter how exasperating it would eventually become. Peering back through those years via the newly discovered correspondence, it’s plain to see how frustrating the situation was to the principals involved.

A letter dated April 4, 1904, was addressed to Col. W.F. Cody at a New York hotel where he was staying on his way to England with “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.” Edward H. Clark, writing on Mrs. Hearst’s letterhead, refused to accept a small partial payment and wrote:

We have carried this matter along for a considerable time, and you will understand that the extensions which we have granted from time to time have been more a matter of personal accommodation to yourself and Mr. Beck than a matter of business, and I feel now that the time has arrived when a substantial payment should be made.

The previous week, Clark had contacted Cody, leaving letters at two New York hotels on the chance the showman would be staying at one of them. He penned:

I notice by the newspapers that you are preparing to sail for Europe. In view of this, I take this occasion to write you in regard to the matter of the bonds of the Shoshone Irrigation Co. held by Mrs. Hearst, and which fall due July 1 next. I beg to notify you that we shall expect these bonds to be taken up when due. I have already notified the company to that effect, and thought it best to also notify you as you have personally guaranteed their payment.

Clark’s concern was justified, especially considering the history of the Wyoming project in failing to meet its obligations. On June 9, 1899, just five years earlier, Clark had written Beck:

The coupons of the Shoshone Irrigation Co. bonds held by this office will fall due July 1 next at the Chemical Nat. Bank this city. Please advise me how you propose to pay these coupons this year. Last year when presented at the bank they were refused and this of course hurts the bonds and I don’t wish to present them there this year if it is your intention to pay them by sending a check to me direct. Please let me hear from you at your early convenience. I am sending a copy of this letter to Col. Cody.

Cody penned a note to Beck on Clark’s letter that said, “My dear Beck, Mr. Clark says if we pay 15,000, one half, he will give us an extension for rest. Be sure and see to this.” Apparently, the Colonel had spoken to Clark before forwarding the note to Beck and sailing for Europe.

Cody queried Beck in a May 11 letter from England, “So did Mr. Clark [say] what the Hearst Estate would do? Please let me hear from you on the subject. Hope there won’t be so much trouble about our ditch this summer,” Cody’s reference to the Cody Canal.

Cody constantly complained to Beck about not receiving sufficient information regarding the conduct of business. A year earlier, he had written Beck from Liverpool, England, “Have been looking for your report for quite a while. Would like to know about the Shoshone Irrigation Co. business. How the canal is, how much land sold, etc. If you will have money to meet the Hearst’s interest, etc.”

(Of particular note is that letters in the newly discovered Hearst cache establish Beck’s borrowings from Mrs. Hearst, or her estate, continued for years after the demise of the Shoshone Irrigation Company in 1908, and after the passing of both William F. Cody in 1917 and Phoebe Hearst in 1919.)

The “Wild West” showman’s ongoing frustration with partner Beck’s management of the venture is demonstrated by excerpts from letters (see below) which until now have been withheld from public view for nearly a century by relatives of George Beck.

Cody’s attempts at management from afar, and his complaints to Beck about the latter’s inattention and neglect, continued throughout the remaining years of their business relationship. From the letters, it appears neither of the two partners had the business acumen and—in the case of Beck, the necessary work ethic—to successfully pursue the demanding project that faced them. Eventually, it fell upon public agencies to complete the Cody Canal.

One can only speculate as to how Cody’s late-in-life financial distress might have been obviated had he avoided a long series of unsuccessful business ventures for which he was ill-prepared. Unfortunate decisions led him and his widow to insolvency at the time of his death.

It was a cruel and inappropriate end for a larger-than-life personage, once the toast of two continents, and, even today, the epitome of the American West.

A Trail of Letters

Lack of formal education is evident in Cody’s grammar, spelling, and punctuation. These handwritten letters, typical in content of those of subsequent years, were mailed by Cody to Beck from along the route of Cody’s 1895 Wild West performances. His frustration with the Cody Canal is clearly evident.

3/26/95—I have no idea what your expenses are this month. Why don’t you ask someone to write me.

3/29/95—From a Union Pacific train: Austin & Co writes me you did not send them the notes I signed. George—have you gone crazy? Get with it, old fellow.

5/5/95—Pottsville, Pennsylvania: Say old fellow are we going to loose [sic] all this summer and get nothing done.

5/7/95—New York, New York: The monied men of our Co want to know what you are doing & if you are going to get water to the town & below…God only knows where you are, and if you will ever get to Cody and if you will get to work when you get there… George. If you don’t try to do something, this dam ditch will drive me crazy.

5/12/95—Scranton, Pennsylvania: Will you put your shoulder to the wheel and hoof things up… We must keep our credit good… Nothing will hurt us more than to loose [sic.] our credit. Will you let me hear from you at once.

6/26/95—Newport, Rhode Island: George, we have got to get someone with money into it… commence work, but I can’t carry the whole scheme & will help you all I can…put your shoulder to the wheel.

7/2/95—Lowell, Massachusetts: Let’s get to work. No more nonsense. I will arrange if possible to help you all I can.

7/8/95—Haverhill, Massachusetts:… while I am at Atlanta Exposition & can with Burke do a world of advertising, I will make that the most talked of place in America. Do you catch on? You sleep just 4 hours a day, no more, till that is a success.

7/24/95—Montpelier, Vermont:… find out the best way to get good title to Land for Town. Take it cool but get there and have things iron bound & lets get to work.

8/13/95—Olean, New York: I cannot make out if anyone put up any money. And if there is any likelyhood [sic] of anyone going to put up—If no one is going to put up what is to be done. Shall we throw up the deal—I & Mr. Salsbury will not carry it alone. And if work cannot be commenced in Sep.—we had better quit.

9/7/95—Altoona, Pennsylvania: Let me know about contract for our land from State Land Board and Interior Dept. We must make no mistakes or we will be laughed out of the country. I depend on you to guard our interests. I trust you. Don’t fail me.

9/15/95—Cortland, New York:… we have got our friends into this and we must protect them. Our everlasting reputation is at stake. All our energy & what brains we possess must be brought into action.

9/16/95—Cortland, New York: If you fellows don’t write me I will quit thinking of you… How I would like to see the dirt a flying on that ditch. Get me a photograph of it.

9/25/95—Newark, New Jersey: You ought to contract for the lumber you want for headgate and we must build some kind of a house for headquarters. But certainly you are attending to these things—For K Christ have someone write me.

10/4/95—Richmond, Virginia: I have written 25 letters at least saying no use to build a little ditch. I came near falling dead & I did some tall cussing when I read your letter about a 15 foot ditch after all the letters I had written to the contrary. If it cant be 20 feet on the bottom call me out. I will quit.

10/6/95—Wilmington, North Carolina:… how many acres can you get water on by first of June. I want to begin to advertise at Atlanta. Get someone to write it up get some photos taken… Hurry up George and have it written up & photos taken.

10/16/95—Charleston, South Carolina:… I understand the Atlantic [sic] Exposition is a failure… I am going to be pressed for cash myself. You have more Foremen than working men. We must make a showing when the men [investors] get there or our gig is up. Now George. Make every man jump to his work & stick to it. Have you ordered the lumber for headgate.

10/19/95—Macon, Georgia: I am uneasy about these things and over anxious as I am getting other peoples money to spend in this enterprize [sic]. And I want nothing done wrong. You are the boss there and My Dear Friend… I will feel awful if money is uselessly squandered there. And no good results to show… If I get out there and these business men sees that the work is being extravagantly done—I fear they wont put up any more money. For Gods sake hoop them up.

10/26/95—Aboard train nearing Atlanta, Georgia: George I don’t see how I can carry this unexpected raise in the estimates… So let no more contracts… Tell them we will do no more this winter. George you bet I am half sick.

10/27/95—Atlanta, Georgia:… I would not have lost that Town site for $25000 in cash. Oh why did you not do as I asked you to. That was to take up the land. Hymer now claims it all. I would like to know what you propose to do… Why did you give him our surveyors to survey a town site for himself when we wanted the town for ourselves? I hope you can fix it up.

10/27/95—Atlanta, Georgia: Alger writes me you have ordered winter groceries etc. If so countermand the order and let no more contracts for winter work Its all too high… Salsbury writes me no business man will now touch it. Now old pard I will do all I can to keep you sollid [sic]… Now George you know the situation and act quick so as to save our credit. I am blue all over.

10/31/95—Atlanta, Georgia: I close here Saturday Nov 2d—Busted. This is the worst place we have struck. No one coming to this Fair. You must close down first or if I cant get new blood in we will be in an awful tight place. Do you appreciate what I mean. I will do my part but get down as easy on me as you possibly can. This I have written you several times

About the author

Former vice president and general manager of KTWO-TV in Casper, Wyoming, Jack Rosenthal has lived in Wyoming since the 1930s. He graduated from the University of Wyoming in 1952 with a bachelor’s degree in history and received an Honorary Doctor of Laws degree in 1993; he’s also won numerous awards within both his educational and business pursuits.

The consummate historian, Rosenthal has genuine expertise with maps, stamps, railroads, baseball, and Wyoming history. He chaired the U.S. Postal Service Citizens Stamp Advisory Committee and designed the Wyoming Centennial stamp and a fifteen-cent postcard stamp of Buffalo Bill, which sold three billion copies. Wyoming Governor Dave Freudenthal also appointed him chairman of the Wyoming Coinage Advisory Committee that was tasked with choosing a design for the Wyoming quarter. Jack and his wife Elaine live in Casper, Wyoming.

Post 214