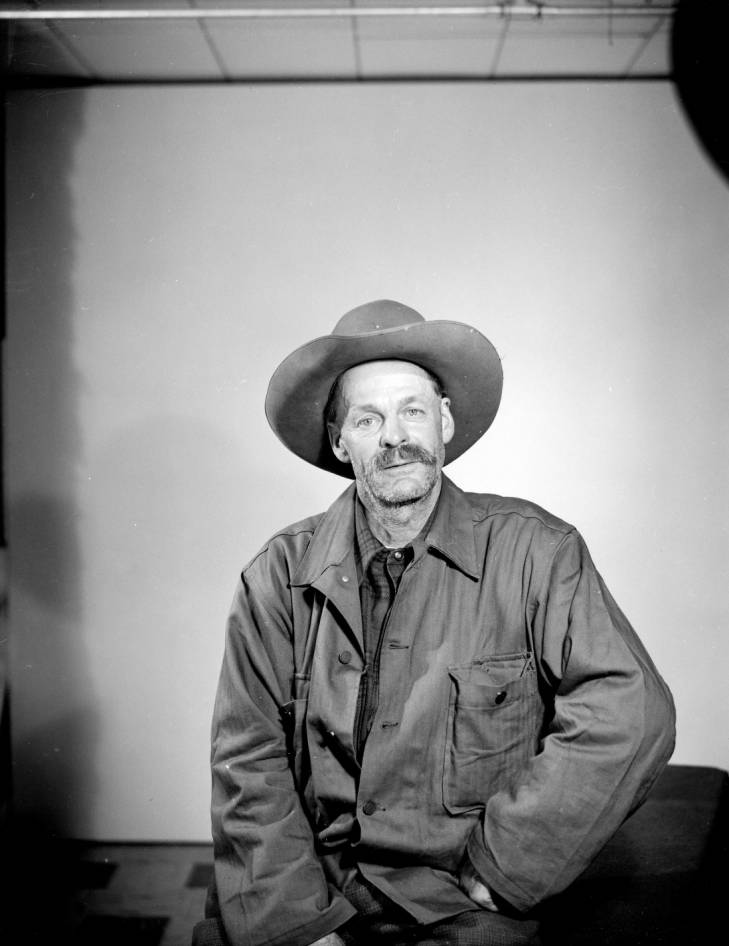

A Future Executive?

When I was doing research on Anson Eddy, I found record of someone by that name working as an elevator operator in Hartford, Connecticut, in about 1920. This guy was going to business school. “That’s odd,” I thought.

“There’s a guy named Anson Eddy, the same as my Anson Eddy, who worked as an office worker in Hartford, Connecticut?” A future executive with the same name as the Cody legend, who lived in the woods, never bathed, and without a car, hitched a ride with the postman, Dean Pond, when he needed a ride to town?

But they weren’t different. They were the same guy. How did a business school student, a trainee for the white-collar world, end up at the end of a South Fork in a small cabin that had a giant stack of newspapers leaning against a stove and a baby bobcat drinking canned milk out of a bowl?

A Secret Government Project

Anson Eddy’s origins are tough to piece together. He was known for tall tales. While a mountain man, he was no hermit, and he liked to tell people he had been born in a teepee in Vermont to an Indian maiden. Huh?

When Pete and Al Simpson were teenagers during World War II, they worked summers baling hay on the T E Ranch. One day they ran into Anson. “What are you doing?” They asked.

Anson told them he was part of a special government project. The Japanese government was sending balloons into the U.S. which would detonate on impact and start forest fires. The idea was that if the Western forests burned up, the U.S. would be weakened. This story turned out to be true.

“Al,” I said. “How the hell did the U.S. government find Anson Eddy? And then hire him?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “I don’t know. We thought it was just another of Anson’s tales, but this one turned out to be true.”

Gone for Good

Anson Eddy evidently found business school a little itchy. He took time off and spent several months working as a forest ranger in Ontario. He resumed his life in Hartford, and a year or two later, he was gone for good.

He took up residence on a bench overlooking the South Fork of the Shoshone River. The place was well situated. With his cabin backed up against the mountains, Anson was protected from the northwest wind, and his cabin door faced the sun. The original cabin isn’t there. It burned down, presumably when the newspapers caught on fire. Anson had a rare coin collection and it turned into a big clog of metal in the blaze. His friends, whom he did not lack, built him a new cabin. This burned down too, and a third cabin, made of cinderblocks, was erected. This still stands today.

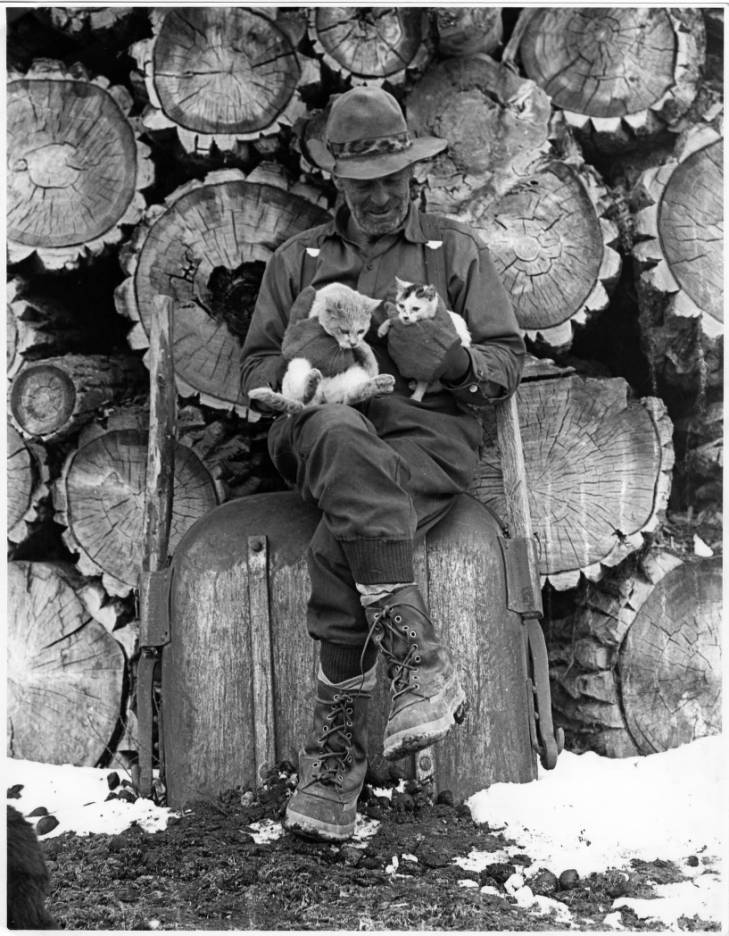

He became a master mountain man. Rawhide tough, every winter he headed into the Thorofare, a wilderness area southeast of Yellowstone Park and miles from the nearest road. He would pack in his supplies on horses, walking the twenty miles or more in his stiff soled logging boots, and turn the horses loose; they headed back on their own. On foot and miles from a road, he would spend the winter trapping pine marten. Grant Gerharter, the South Fork game warden, was patrolling the Thorofare when he found a stash of Anson’s traps cached under a lodgepole pine. He took one as a souvenir, but left the rest.

“They put a lot of pressure on him to become a professional person”

When Anson Eddy died in 1982, his funeral was held at his cabin on the South Fork, and there was quite a turnout. One of them was Anson Eddy’s brother, a retired college professor who lived in Arizona. He said to Al, “Our folks were just too hard on him.”

“What do you mean?”

“They put a lot of pressure on him to become a professional person,” Anson’s brother said. “It was just too much for him and he just freaked out, and came out here.”

Anson Eddy willed his property to about thirteen different people, so it couldn’t be subdivided. In the summer you can find campers and things, when they go down there to fish. Anson’s grave is there, along with his cinderblock cabin, which still stands.